After last year’s instructive and inspiring viewing of Steven Spielberg’s entire oeuvre, I decided to tackle the entire work of another filmmaker I like. In January, I watched Blood Simple, and thus began my journey through the works of Joel and Ethan Coen.

We’re in a Tight Spot!

My history with the Coens isn’t akin to mine with Spielberg, whose work is foundational to my creative interests. I liked the Coens, had seen the majority of their movies, albeit usually just once, as contrasted with the, say, six-thousand times I’ve seen Jaws or Jurassic Park. And because I’d mostly just seen their movies on or near release (starting with Barton Fink in 1991), I didn’t have the overview of their career that I had with Spielberg. I didn’t know what makes them tick, where their interests lie, how they’d grown or matured or evolved as filmmakers.

Turns out, I didn’t need to watch all of the films they wrote and directed to learn that.

Because if you’ve seen one Coen Brothers movie, you’ve kind of seen them all.

I don’t write this to disparage the Coens! I sincerely enjoyed most of their movies, and even the ones I didn’t, I could recognize the obvious skill with which they were made. (I mean, except those two; you know which ones).

Joel and Ethan Coen burst out of the gate in 1984 with Blood Simple fully formed. Their obsessions, tics, and considerable technical skills were present from the start. Over the next 33 years, their budets went up and down, they worked in a few different genres that clearly inspired them to become the filmmakers they are, sometimes they leaned toward comedy, sometimes toward drama, but usually their work is some wryly absurd middle ground that is distinctly their own. Even when working with Western or screwball or noir tropes, the Coens are a genre unto themselves.

Which made this exercise of watching their films kind of a frustrating one. I will never be able to do what the Coens do. No one can.1

A World of Pain

Part of my letdown comes from not so much a clashing worldview with the Coens but with how that worldview makes for a good story. The parameters of their philosophy are incredibly narrow, and their worldview never really expands. I can’t help but compare this with Spielberg, and I wonder if it’s because the Coens are self-generating filmmakers. They write and direct their own material, where Spielbs (mostly) only directs the works of other writers. Thus, Spielberg is forced to confront, if not conflicting then at least differing worldviews and figure out how he can take those into account while still making “a Steven Spielberg film.”

The Coens’ philosophy is best summed up in this scene from No Country for Old Men.

The Coens adhere to a doctrine that the universe is random. If karma exists, it’s mercurial. Bad things happen to good people and good things happen to bad people and every permutation thereof. The endings of almost all of their movies illustrate this idea. Sometimes tragically, sometimes comically, usually somewhere in the wry, slapsticky middle.

Ironically, it’s not a worldview with which I disagree! Trying to find meaning in the universe is pointless. I just don’t think that philosophy always makes for compelling storytelling. Especially between 2001 (The Man Who Wasn’t There) and 2009 (A Serious Man), the inevitable tragic chaos of their worlds felt smug, cynical, or just depressing.

Even Burn After Reading, which I mostly enjoyed, is another example of the more apparent cynicism and misanthropy in the Coens’s work post-O Brother which makes it hard to care about anyone. Why should I care if they don’t?

As I wrote in my Letterboxd review of No Country for Old Men, “their movies don’t grow deeper or even, despite different genres, play different notes. But there’s such a sense of anarchic glee in everything leading up to Fargo and O Brother (which I think are their masterpieces). I wish they’d discover new tools or get excited about new ideas.”

Folk Songs

I don’t mean to sound down about the whole endeavor. As I said, I did enjoy most of the movies. There are a lot of pleasures to be found in the Coen Brothers’ films. They have two incredible runs, between their first film, 1984’s Blood Simple and 2000’s O Brother Where Art Thou? and then again with the one-two punch of True Grit (2010) and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013).

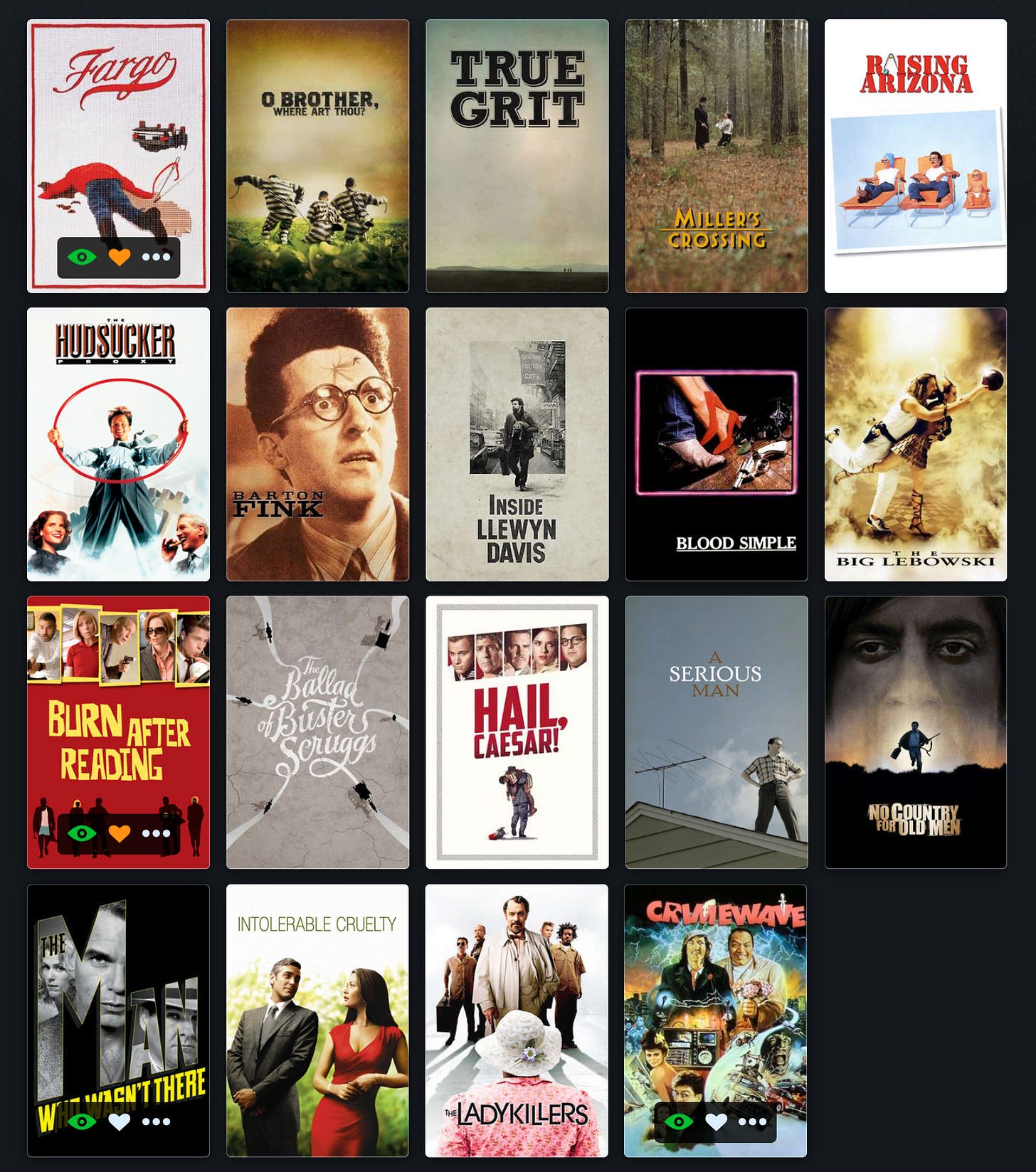

Here’s my ranking of all of the movies (including the abysmal Crimewave, which the Coens wrote and Sam Raimi directed and about which I wrote “it’s wild that Raimi and the Coens were ever allowed to make anything again.”)

Those first four are for sure my favorites, but I genuinely love The Huducker Proxy, Barton Fink is bananas and it’s incredible that it even got made, and Llewyn Davis is a really special movie. On this viewing, I really enjoyed both Raising Arizona and The Big Lebowski, two movies with which I’d never really connected. Both are wildly funny but also have terrific grounding performances, amid the Coeny weirdos, in Holly Hunter and Jeff Bridges.

Blood Simple must have been a shotgun blast to the gut for anyone who saw it in 1984. It feels simultaneously like it could have been made a decade later and like it came from the 1950s. Truly, there would be no Soderbergh, Tarantino (obviously), or Fincher without this movie and, I suspect, the first decade of Coens.

I think this timeless—or maybe “outside of time”—quality is what makes the Coens such singular filmmakers. Llewyn Davis’s description of folk music is sharply applicable to the Coens’ own works. I’m leaving this in with the full song because, hell, it’s just a stunner.

Apologies for the Russian (?) subtitles. This is the only version I could find with the line of dialogue I needed. Quick sidebar: while I was searching around for this video, I turned up this video of a young Rachel Zegler, three years before Spielberg’s West Side Story, playing an earnest and adorable cover of this song. I didn’t know Zegler was a YouTube channel kid. It’s endearing.

I’m a Dapper Dan Man!

So, I guess this is something to take away from these films, something to aspire to.

It’s about voice.

Is that the lesson that Llewyn learns at the end of the movie? Inside Llewyn Davis is (I think) the Coens’ most self-reflective film. It’s hard not to read into the story of an okay creative talent who both can’t get a break and can’t get out of his own way. (Or maybe I just relate too much?)

Oscar Isaac brings the full breadth of his humanity to Llewyn, as we follow him around New York, crashing on couches, making mistakes, singing and playing the music he clearly loves. In the last scene of the film, Llewyn sings that lovely song, and is followed on stage by an unnamed folk singer.

The Coens make no secret that this is Bob Dylan, as the singer launches into “Farewell,” a well known Dylan song. The voice is unmistakable.

Bob Dylan never had a #1 hit, but his is a voice that started a revolution. Like the Beatles just before him, he sent music careening off into a new direction. He’s everything Llewyn would never admit that he wants to be.

And it’s because no one can do what Bob Dylan does. His is a singular voice, as a singer, yes, and as a songwriter too.

I can’t do what the Coen Brothers do.

But I can do what I do. So I guess I’ve found some inspiration from the Coens after all. A happy ending. They’d hate that.

Noah Hawley can a little bit.

Correction: if you've seen TWO Coen brothers movies, you've seen them all. They have their two modes: wacky (Burn After Reading, O Brother Where Art Thou, Hail Caesar etc) and serious enough to get Oscar noms (Fargo, A Serious Man, True Grit etc).

And I'd love your deep dive on Wong Kar Wai! In 2021 my local cinema was showing one of his movies each weekend, and being immediately post-covid lockdowns it was an exciting thing to get to go, so I've seen all of them. I certainly don't recommend all of them. But the good stuff is so good, and his recurring motifs are so...motif-ey, and his working methods so unusually improvisatory; our Wong Club was such an interesting thing to do.

MILLER'S CROSSING is, IMO, their best film. I find something new in it every time.

The other thing I wonder is why so many of their movies are set in the past. It's as though they're both nostalgic for the old days and yet clear-eyed about how bent things were back in the day.