Let's Talk About Specs

What to Write, part 1.

Paid-Sub-Exclusive Q&A Guest Announcement!

As I’ve mentioned, paid subscribers (I should come up with a name for these supporters. “Write Club?” Please weigh in) will have exclusive access to Zoom Q&A conversations with pro writers. I’m thrilled to announce that our inaugural guest will be C. Robert Cargill! Cargill is a screenwriter and novelist who started out, like so many of us, as a fan. He was a reviewer for Ain’t It Cool News and other outlets for many years before breaking in with the terrific Sinister in 2012. He has since written, with collaborator director Scott Derrickson a sequel to Sinister, Marvel’s first Doctor Strange movie, and most recently, the terrific adaptation of Joe Hill’s The Black Phone starring a terrifying Ethan Hawke.

I’ve been lucky to hang out with Cargill a few times in Austin, where he lives, and I can genuinely say that there are few who love talking about writing, and hanging out with creative people, more. He’s going to have some incredible insights for those lucky enough to attend and ask questions.

Fittingly, the Cargill Q&A will take place Halloween weekend. Further updates to come. This Q&A will not be made available to the public, and the only way to hear it or attend is the become a Write Club member. (Yes, I’ve decided on Write Club).

The Specs Talk

I love when the Specs vs Originals argument arises because, like all Writing Twitter disagreements, it’s utterly ridiculous. The bottom line? Write both. They’re valuable in different ways.

Until around 2010, the common practice for writers who wanted to get into the TV business was to write a “spec script.” That is, a sample episode of an existing show. This was before the TV landscape became so fractured. Until the rise of streaming, everyone generally watched the same shows at the same time, so you were pretty safe speccing a show that was popular. Seinfeld, Friends, Fraser, The Simpsons, Law & Order, The X-Files, and a few others were shows to spec as I was coming up.

I loved writing specs. Foremost, it’s because I love the shows I watch, and spec scripts are basically fan-fic. In our first week working together, Acker and I wrote two spec episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, our favorite show then on the air. One of them essentially took place at our Syracuse University coffeeshop hang-out.

The other reason writing specs is so valuable, and I’m glad that fellowships and writing programs still require it, is because it essentially sets you up for the job of being a writer on the staff of a TV show.

As Kenya Barris, the creator of Black-ish, says, he’s hiring a staff to help him write: “I’m going to pay you, and I’m going to pay you well, but I need help. I need you to know these characters’ voices and to emulate them. It’s amazing that you have your own voice, but [you have to be] able to funnel your energy and your voice through the characters you are going to be hired for.”

Victor Fresco, who's written for and created lots of shows including Santa Clarita Diet and Better Off Ted, says he would never hire someone based upon an original sample. “It doesn't tell the showrunner anything,” he says. “You're trying to show how well that person can find your voice, not what their own voice is.” Fresco, when he started out, wrote specs for Head of the Class and Family Ties.

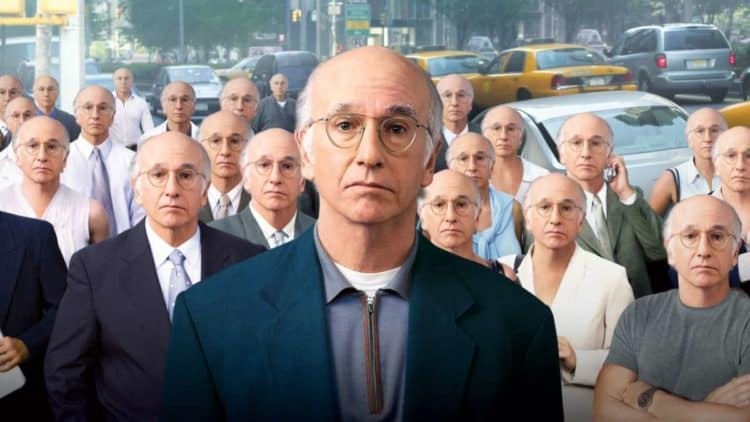

“Some of the best episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm that I’ve read don’t exist,” says Halo showrunner Kyle Killen.

It’s always fun for me to ask Writers Panel guests about their early spec scripts because they’re often so telling about both the time in which they were written and the charming naivety and enthusiasm of the new writer who just loves TV.

Kenya wrote “ten or eleven” specs “and just kept writing” to learn his chops. Among them were a Just Shoot Me and this Seinfeld spec:

George was on a plane, and there was a guy who was fancily dressed next to him. And he spilled orange juice on his lap and basically molested him...cleaning it up. Then the guy offered to pay for it, and George started a relationship up with this guy. And it was like, “Are you dating this guy?”

Steven DeKnight, showrunner of Spartacus and Jupiter’s Legacy, wrote “a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine that explained why Ferengis were short.” The spec got him a job on MTV’s teen sex comedy series Undressed; the showrunner was a huge Deep Space Nine fan. And when Steve wanted to transition into prime-time dramas, he wrote a new spec for his favorite show at the time, Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Taking a page from my Ferengi script, I wrote a script called “Xander the Slayer” which explained why men can’t be slayers. Because basically the power goes to our big fat heads. And we go bananas.

That eventually led to a job on the staff of Buffy’s spin-off Angel.

One of my favorite specs is by David Iserson, co-writer of The Mentor and The Spy Who Dumped Me. When I put out a call to help Adam Mallinger (fka Bitter Script Reader) collect specs from pro writers, David wrote to me:

The only spec script I ever wrote was a Seinfeld when I was seventeen. It’s set in the Revolutionary War for some reason.

I love that Adam Mallinger compiled as many of these specs as he could get his hands on. They’re all here, including David Iserson’s Revolutionary Seinfeld.

I don’t think David’s Seinfeld ever made the rounds as a sample, but I love that it exists and is the most him spec he could write. Which is why specs are so much fun.

But it’s the process behind writing one that’s most valuable. The nature of writing a good spec is that you have to study the show you’re writing, break it down into it’s component parts, and reassemble it into something of your own devising.

I remember when Acker and I wrote our Will & Grace spec one hundred years ago. I wasn’t really familiar with the show, but it was the sample our agent at the time wanted. So I analyzed episodes more dilligently than I ever studied for a test in high school or college.

Doing this, you wind up reverse-engineering an episode to, as Richard Hatem (Titans) says, “to suddenly see things emerge. Like if we could take the walls down and you see girders and you’re like ‘Oh my god, that’s what’s holding this place up’!”

The great Jane Espenson, master of craft, puts it directly:

If you really want to be a TV writer, the best thing to do in recreate the outline we wrote the episode from as you watch the episode.

This reverse-engineering process isn’t valuable only for specs.

Michael Green (Blade Runner 2049) learned to write TV by reverse-engineering episodes of Friends.

I sat there transcribing a Friends episode and was like, “There’s an A, B, and C story!” I literally sat there with a VCR, like rewinding, going, “Wait a minute! And then there’s this Phoebe D-runner! What do we call that! A runner!”

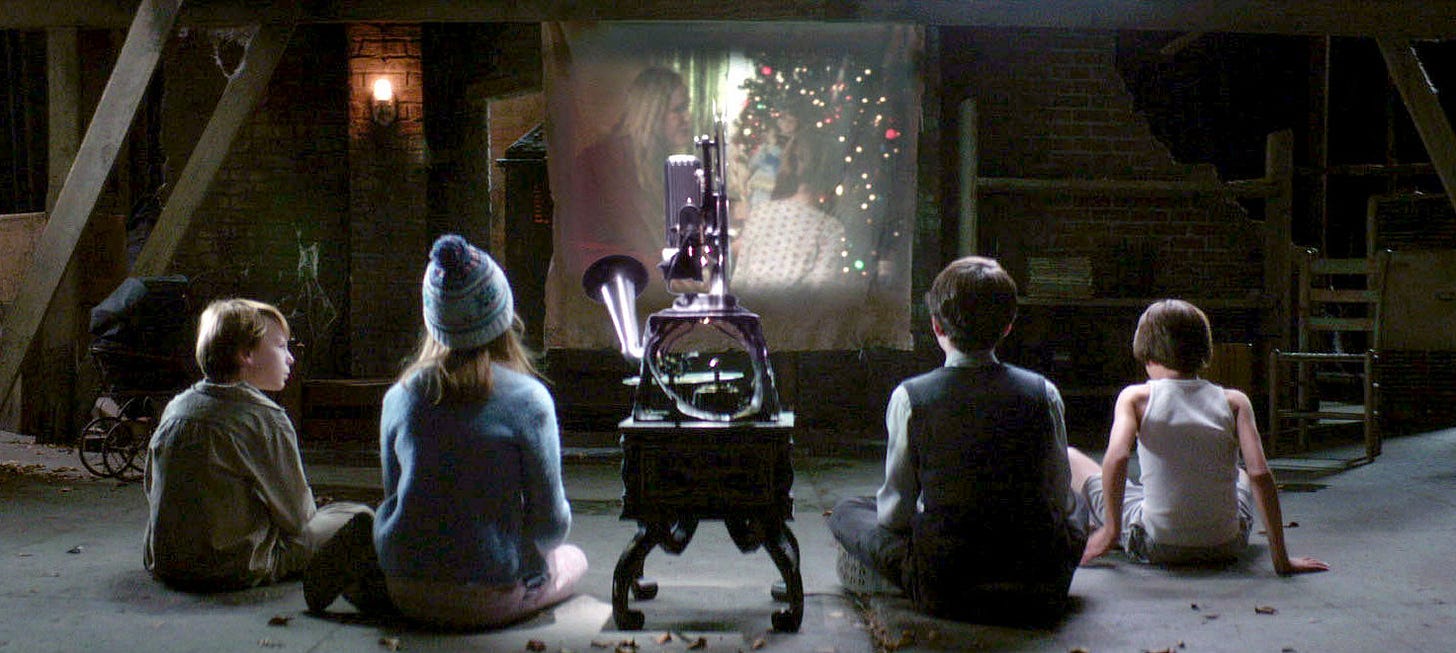

Even if you’re working on an original sample, it’s helpful to reverse engineer comparable shows. A few years ago, when I was working on a very dark and personal horror pilot, I knew I wanted it to tonally sit side-by-side with Mike Flanagan’s brilliant The Haunting of Hill House series. So I watched and rewatched that Hill House pilot and wrote down how each story was moved along—plot-wise, emotionally, scares—scene by scene, act by act.

I just went looking for those notes to post, and while I couldn’t find them, I did stumble on my deconstruction of two Buffy episodes from maybe 1999 or 2000? These were after Acker and I wrote our specs. I believe I reverse-engineered a couple of episodes when we were working on an original pilot that we wanted to be be Buffy-like in tone. I analyzed episodes 1.3 (“Witch”) and 2.7 (“Lie to Me”).

So, your homework for this week is to figure out what you’re writing next. Is it a spec of an existing show or an original? Watch a few episodes of the show you’re speccing, or pick a couple of episodes of a show tonally and structurally similar to the original you’re working on. Go scene-by-scene and write down the ways in which the character/plot/genre stories move forward. Sometimes these will overlap. Often they won’t. This process will take about twice as long as each episode.

Once you have that breakdown, look at how it applies to your script or outline. Are you following the structural pattern established by the show? If not, are you breaking that pattern for a good reason and does it still feel like the show? If not, how can you re-address your outline so that it’s more in line with the tone/structure of the show you’re speccing or emulating?

The best part of this homework, maybe the best part of being a TV writer, is that watching TV is part of the work.

All right, that’s a lengthy one, so thanks for reading. Next week I’ll have our first Write Club-only newsletter! Join now for that and access to the upcoming Q&A with C. Robert Cargill, and more!

And please leave a comment letting me know what you’re working on! I love to hear about it.