Hold Onto Your Butts

If you’ve been following the newsletter, you know that this year I’ve been on my #Spielberg2023 journey, in which I’m watching (or rewatching) every movie that Steven Spielberg directed (or executive-produced, up til about 1990). I’m tracking it all on Letterboxd, if you’re interested in how some of these hold up.

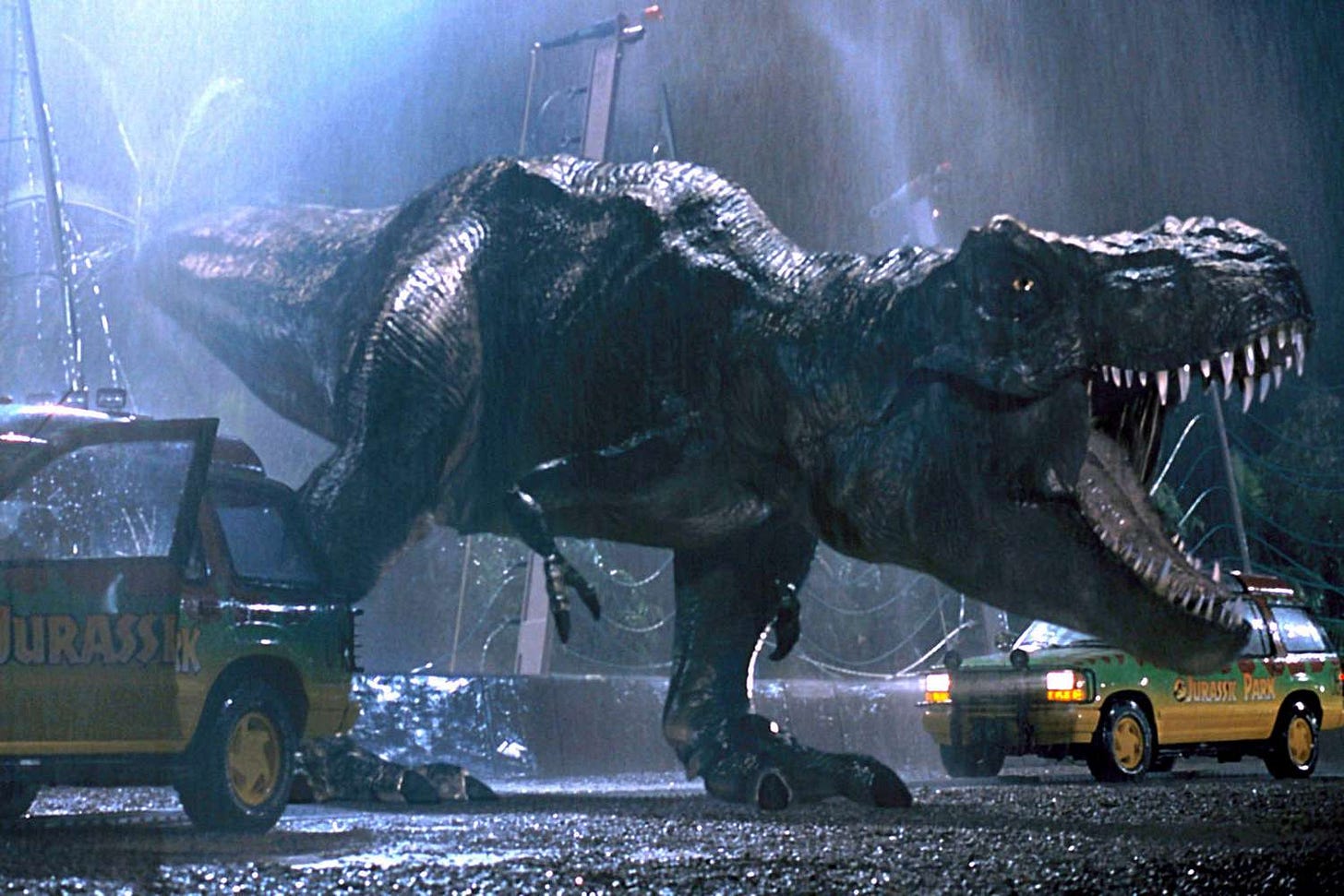

I’ve just finished up what I consider Spielberg’s second great era of filmmaking. Between 1993 and 2005—a stretch twice as long as his initial hot streak that began with Jaws and ended with ET—Spielberg knocked out ten films, no fewer than half of which are iconic. 1993 saw the dual release of both Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List, two movies in which both the director’s unmatched technical prowess and passion for personal storytelling came to a head. He followed those with a string of films remarkable as much for the varied subjects, sizes, and modes of storytelling, but also because this was a director clearly reveling in pushing himself toward deeper, more interesting, more technically advanced work. Not always successfully; Amistad (which is better than I remembered), the Jurassic Park sequel (which has a few truly great set-pieces), the fascinating Kubrick-Spielberg mash-up of AI: Artificial Intelligence, and The Terminal (emotionally effective, at least) are not terribly calamitous bumps in a pretty incredible stretch that otherwise includes straight up masterpieces like Saving Private Ryan, Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, and War of the Worlds.

(I swear to you: War of the Worlds is an incredible artifact of post-9/11 trauma catharsis and a cracking good action movie with an all-time Tom Cruise performance).

None of which is terrifically important to the thing I want to talk about today, but, given the opportunity to write about my Spielberg movie bullsh, I’m gonna take it. It’s my newsletter.

Dino Score

What struck me most about the movies of this era is just how good the scripts are. Schindler’s List by Steve Zaillian, Saving Private Ryan by Robert Rodat, Minority Report by Scott Frank and John Cohen, Catch Me If You Can by Jeff Nathanson, War of the Worlds by Josh Friedman and David Koepp… These are all miles better than most of the screenplays from which Spielberg worked in the decade previous. The best of all of them, I think, is David Koepp’s script for Jurassic Park.

The Jurassic Park script is brilliant in so many ways, but what I noticed most in this rewatch is just how good Koepp is at exposition. There’s a lot of both science and character stuff to get across in the first half of the movie, and it needs to be both intellectually and emotionally understood so that the second half—when the dinosaurs wreak havoc—hits hard.

Exposition can be so difficult to write. As Reacher and Scorpion creator Nick Santora told me, “You have to do exposition. And you know it hurts your ears, so you try to make it as non-painful as possible.”

Exposition is frequently the enemy of drama. It’s the dry information that your audience needs in order to understand and engage with your story. How this story’s version of time travel works. What that character’s backstory is and why it drives them to chase serial killers. How we’re able to clone dinosaurs. It’s the material that needs to be handled deftly, “otherwise,” says Stan Against Evil creator Dana Gould, “you get lines like, ‘How long have we been brothers’?”

Since exposition is an unavoidable aspect of screenwriting, I’m going to spend the next few newsetters highlighting ways you might tackle it, using Koepp’s Jurassic Park script as example.

Find a Way

Probably the most important kind, which we don’t always think about as exposition, is character-related. Sometimes it’s backstory, which execs will always ask for more of.

I recently talked with May December writer Samy Burch for the podcast (it’ll be out in January), and I asked her about doling out backstory in the movie; I thought it was handled deftly, through conversation. She described starting her process by writing character bios, just a couple of pages long. Information from those bios then make their way into the scenes when they need to, in a natural way.

Musicals—particularly Disney musicals—have the “I Want” song. A known trope on Broadway, songwriter Howard Ashman descibes it thusly, in discussing his song “Part of Your World” from The Little Mermaid:

In almost every musical ever written, there's a place that's usually about the third song of the evening... and the leading lady usually sits down on something; sometimes it's a tree stump in Brigadoon, sometimes it's under the pillars of Covent Garden in My Fair Lady, or it's a trash can in Little Shop of Horrors... but the leading lady sits down on something and sings about what she wants in life. And the audience falls in love with her and then roots for her to get it for the rest of the night.

I assume most of you are not writing musicals, but think of the “I Want” song as establishing your character at the beginning of their journey. Jurassic Park gives a great example of an “I want” scene (more of an “I don’t want” scene) that’s a double-whammy: it’s preceded by a pure exposition scene that tells us how scared we should be of velociraptors.

In the first part of the scene, Alan Grant (Sam Neil) describes exactly how velociraptors hunt and kill, information we’ll need later when those bad girls show up. We even get the line establishing that the T Rex’s vision is based on movement, also info we’ll need later. But we don’t even notice these info drops because the scene is so engaging. It’s funny because this isn’t how you talk to a child; it’s filled with tension, because we don’t know Dr. Grant well enough at this point to know how this will play out; it’s based in character (the kid has established himself as a brat who disrespects dinosaurs; Grant has established himself as someone with utmost respect for dinosaurs); and it’s visually interesting, as Grant walks around the kid and fake-slashes him with the raptor claw.

We also get a reaction shot from Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern), who is Grant’s colleague and romantic partner. She shakes her head and mutters “Oh Alan,” suggesting that this is very much in character for her boyriend.

Sattler takes center stage in the second part of this scene, which is Grant’s “I don’t want” song: the exposition establishing his status quo. In one minute of dialogue that is funny and charming in a way that speaks to their relationship, we get that Grant does not want children and Sattler does. It’s a scene filled with conflict that doesn’t play out as an argument. It’s clearly a conversation they’ve had before and one that’s been back-burnered as they go about their work. And then, smartly, the scene is interrupted by a helicopter invading the dig site before any conclusion can be made.

Through dynamic exposition in the first nine minutes of the movie, we understand that Jurassic Park will be the story of Alan Grant wanting to become a parent. His experience on the island is the journey he must go through to have his worldview altered.

I chatted with writer/director Jenn Kayton Robinson after the debut of her terrific first feature Someone Great. The second scene in the movie—literally two minutes in—finds Jenny (Gina Rodriguez), drunk, setting up her backstory with a stranger (the amazing Michelle Buteau):

I asked Jenn why this was the best way to convey the information we needed to understand Jenny’s status quo. She described a different cut of the movie, in which this scene plays after the credits (which show Jenny and her ex’s love story through social media posts), but that version “didn’t tell the story of the movie you’re watching.”

That is, this isn’t a movie about this couple getting back together. And indeed, the opening scene (a flashback to Jenny and her ex in happier times) followed by this scene played “back to back,” says Jenn, forms a mission statement. “It’s the whole movie. This is the ride you’re about to go on.”

There’s something so weird and New Yorky about Jenny sitting on the subway,, talking basically to herself and then this woman being like, shut the fuck up. And then her taking that as an invitation to tell her how bad her night was. So, yes, it's exposition, but it's exposition from place of character.

Next Time:

Dinosaurs on our dinosaur tour.

Yule Love This

As I was looking at the lists of “I Want” songs, I was reminded of a great one from a movie that’s been criminally overlooked.

I am not a fan of musicals! But I do love horror movies and I do love Christmas movies, so Anna vs the Apocalypse checks enough boxes for me. It’s a zombie rom-com Christmas musical, and is so charming and funny and gross and smart. The script by Alan McDonald and Ryan McHenry is tight and sharp, and director John McPhail makes so much of what I’m sure is a limited budget. The songs, by singer/songwriter Roddy Hart, are bangers, walking the line between Broadway artifice and indie music (and indie film) cleverness. And Ella Hunt (who would later be equally amazing in Dickinson, another underrated gem) as Anna carries the whole thing with such charm, intelligence, and wit. It’s a really fun movie and a great one for the holidays, since you’ve rewatched Die Hard and Elf so many times.

As long as we’re down this rabbit hole: Ryan McHenry wrote the short on which the movie is based and is credited as co-screenwriter. He previously found viral fame in 2013 with a series of Vines (remember Vine?) called “Ryan Gosling Won’t Eat His Cereal” which were so ridiculous and funny.

McHenry sadly passed away in 2015. If you had any doubt about Ryan Gosling being a sweet guy and more than just Ken, know that he created a Vine channel just to pay tribute to McHenry. You can see that here, along with the backstory.

Anyway, send me your overlooked Christmas movie recs!

Stealing 'How long have we been brothers' for the title of some French drama, or extremely silly comedy - haven't decided yet.

This is so awesome!!! I'm a musicals fan and have long loved the I Want song, but I like this idea of there being an I Want scene too.

An as far as Christmas movie recs--definitely Scrooge (1970) with Albert Finney. He is incredible.