Fail Safe

Plus: the Matt Nix Q&A recording

Why's everybody always pickin' on me?

I’ve been thinking about failure a lot lately. Which makes sense, with the industry behaving (or misbehaving) the way it is. It feels like things have ground to an absolute standstill. This is, as an exec I met yesterday said, “on top of the standstill we’ve had for the past few years.”

It’s hard not to feel like it’s personal, though. That the execs and editors who ghost you, the unreplied-to emails, the meetings you don’t get, are because of you. Your lack of talent, your terrible personality, that you’re not pretty enough.

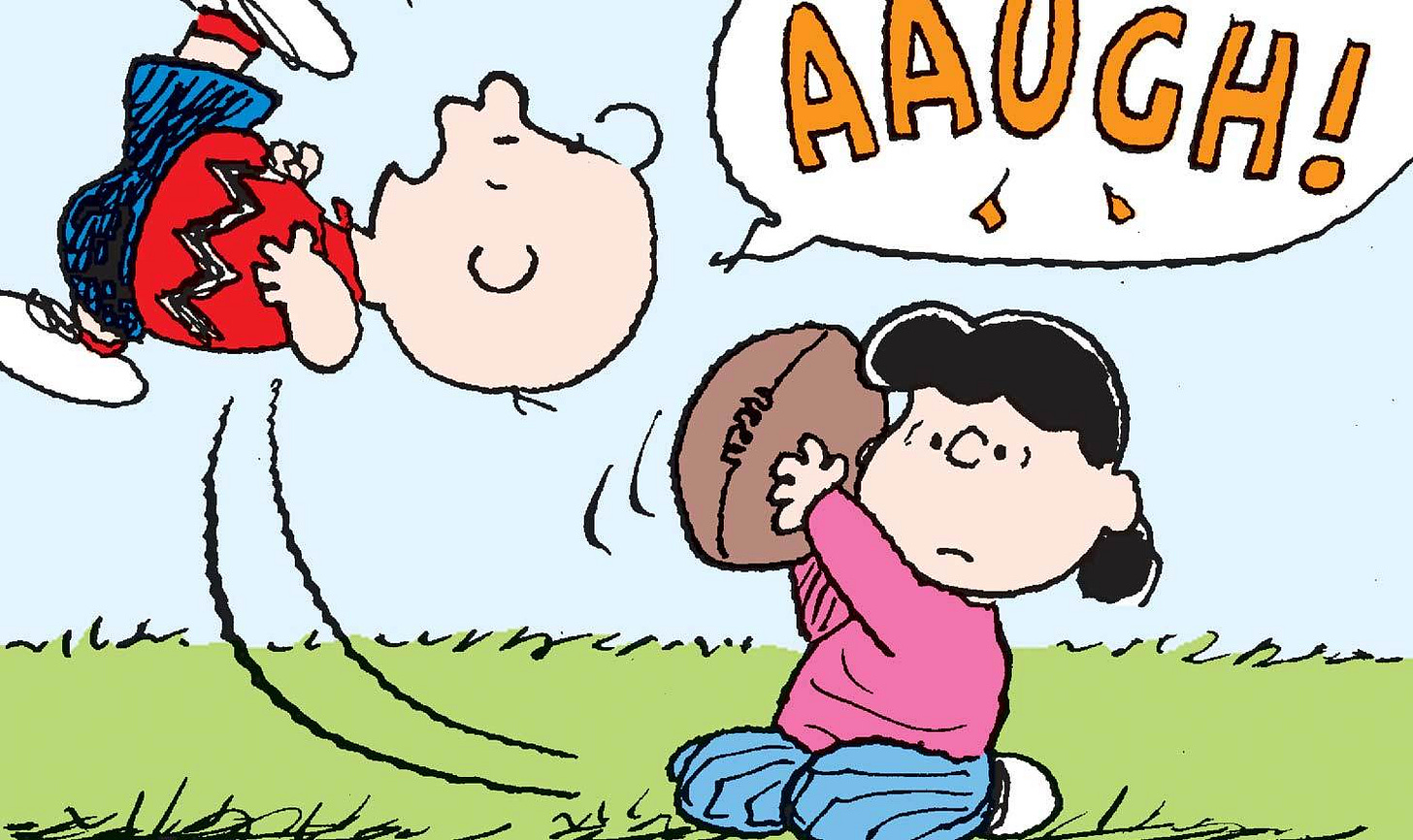

Failure is the bedrock of the entertainment industry. You’ll have more failures than successes. But we’re like Charlie Brown staring down that football that Lucy promises she won’t pull away. We believe her every time.

Failure Made

The amount of rejection in entertainment is not for the easily shaken.

“If you don't know how to get comfortable with failure, uncertainty, rejection, critiques, critiques by morons, then it’s really, really hard to get up every morning,” says Dan Gregor, the co-writer of last year’s really fun Chip 'n Dale: Rescue Rangers movie. “Your stomach's in knots over it.”

The key to dealing with the non-stop failure of the industry seems to be to use it as fuel.

“A good failure or a good screw up is pretty good for your character and your career if you come through it,” Chris Chibnall, the creator of Broadchurch says. He’d had a not-too-fulfilling experience on a show called Camelot and came out of that “feeling that I really wanted to reclaim my territory as a writer. I needed to do something more personal to me, a passion project for me. And so I wrote Broadchurch on spec for myself.” That show changed the direction of his career. Most recently, he was the showrunner on the last few years of Doctor Who.

My So-Called Life creator Winnie Holzman, co-wrote a stage musical early in her career that got terrible reviews. She talks about how that changed her way of thinking.

“When you have a big failure, it can be actually the best thing that can happen to you. In my case, I had to ask myself... “Was that why I was doing it? For the reviews?”

What I was actually doing? What was my actual goal? It took me months… I actually questioned if I was a writer and if I was even cut out for it. But when I got through the whole questioning process I felt a lot better. I had more of an understanding that I wasn’t really that interested in what a bunch of people that wrote for magazines that I would never meet thought of me. I actually felt a little stronger.

It was just after that experience that she met Ed Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz who were running the third season of Thirtysomething. Because of the soul-searching she went through after that musical failure, Winnie was unafraid to ask them for a freelance episode of the show and was eventually hired on staff.

Wash Up Not Out!

“The common denominator in so many people that I've worked with,” says Bill Hader (Barry; SNL), “is how you deal with failure. Just, you just keep moving forward. You're just compelled to do it [even when] you fail.”

It’s good advice, but sometimes feels like impossible advice to follow. Like, how do you deal with the constant barrage of failure? Is it, like Winnie Holzman says, finding something to learn about yourself or your craft or the business from that failure?

“I tried to staff before I sold a movie, before I ended up with my own shows,” says Halo creator Kyle Killen.

I wrote a Law & Order spec which I thought was very competent, and it seemed to me exactly like an episode of Law & Order. I sent it out, and everyone who read it said, “that is exactly what it is.”

And I said “...so when do I get a job?” And they were like, “we already have those people. We don’t need more people who can make a Law & Order episode. Unless you can do something they can’t, we don’t have a place for you.”

What Kyle learned from the failure of that sample to gain traction is that you have to “prove that you bring something that nobody else had.” He learned, in features, that “I didn’t have to pretend that I could follow the path and write volcano movies because they’re hot at the moment. It was just: do whatever the fuck you want, do something that means something to you because you’re going to waste your time doing it anyways. It should come from you.”

Is the answer just acceptance that failure is a constant, overwhelming part of working in this industry? I think it might be.

So does Ed Solomon, screenwriter of the Bill and Ted movies, Men in Black, and Mosaic: “You’ve got to be comfortable with living in what they call the ‘not knowing space’, which is hard,” he says. “And you have to let that into your life and not react against it by trying to avoid it or countering it.”

Solomon says, “you have to be aggressive with yourself. And you've got to honor your own ability to fail, and the necessity to fail, and not let that get you down, but rather to understand it’s part of the process. Then it becomes a question of: how much patience do you have? Because it takes patience for all of us, at every level, with everything.”

Treasure Hunt

That’s “Verb→Noun.”

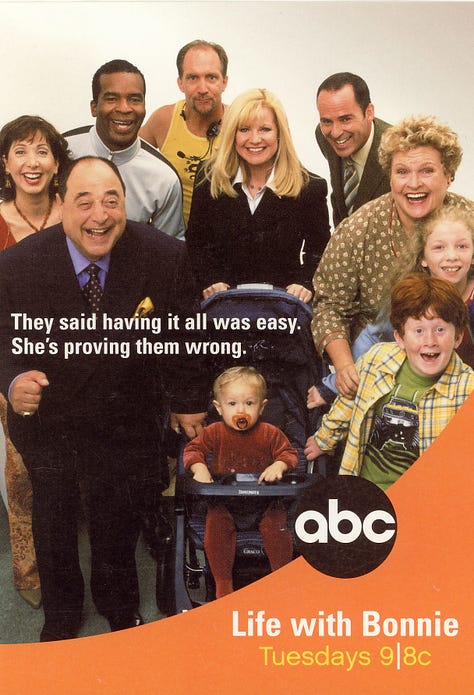

I’m a longtime Bonnie Hunt fan, from her appearances on Letterman to her early nineties sitcoms which had the rhythms and character-based jokes that were unlike anything on TV at the time. I was absolutely thrilled to get to talk to her last year for the podcast, when her Apple TV+ show Amber Brown premiered.

Bonnie started out as a nurse in her hometown of Chicago, all while taking classes at Second City and wanting, more than realistically pursuing, a move to LA to become an actor.

I had a cancer patient say to me that the biggest regret of his life was that he feared failure.

So he said, “take my hand and look me in the eye.”

I said, “okay.”

He goes, “promise me, when I'm gone, you'll go to California and you'll fail many times.”

And I said, “You have a deal.” And yeah, after he was gone, I went to California and I failed. Many times.

Like Kyle, Ed Solomon, and Winnie, Bonnie talks about emerging from failure.

Early in her career, she worked as an actor on the sitcom Grand, which was a very funny, smart show. But the network wanted a lot of changes, “and then the writer kept adapting the script to kind of match the notes, match the notes, match the notes, and then the network came to him and said: we don't like the show anymore.”

It was, she says, “a valuable lesson for me to see that writer painfully get judged by somebody else’s standard. And that's why I always say that failure by your own standards is a form of success.”

That’s the part that I need to embrace.

It’s an idea that I keep coming back to in these newsletters: make the thing that I want to make. It’s so easy to second-guess yourself or feel like it’s hopeless or pointless, because you’re not selling or you’re not getting a greenlight, or you’re not even getting up to bat.

I have to remember that I can, even if it’s just on the page for now, write the story that I want to see. I can bring that thing into existence. And that’s enough for now.

Heart of Nixy

Below is the recording of Sunday’s Q&A with Matt Nix, the creator/showrunner of True Lies, Burn Notice, The Gifted, and more. This was an incredible conversation with Matt. There’s so much terrific, practical advice about both the craft and business of writing, great stuff about networking and reaching out to showrunners. Thanks to everyone who showed up to ask questions.

If you want to give it a listen, and join our next Zoom Q&A on April 22nd (guests—yes, plural—announced soon!), just upgrade your subscription now:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Re:Writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.